I’m really not sure what drove me to shell out cash for this game. I had never heard of it - I merely was interested in the thumbnail and clicked through. There was a free demo - I did not try it. While it was on sale, it was only a small discount and is now the most expensive game I’ve bought since 2019, when I purchased Disco Elysium. Not exactly a price tag I would impulse buy without doing prior research. That said, I did buy it, and I’d like to offer it up amongst the crowd of games in particular because it’s the kind of game that I don’t think would be on anyone in my circles’ radar. It certainly wasn’t on mine, and it ended up being a real treat.

Motesolo is an interactive film - it combines the tropes, style, and language of a Korean Drama (KDrama) TV show with the branching, difficult choices of interactive games like The Dark Pictures Anthology games or Life is Strange. I mention the latter examples because this game stands rather unique amongst interactive-film-type games. Because the medium depends on the player making tough, heavy decisions, these games are usually dominated by serious or thrilling subject matter. I’ve generally avoided these types of games because they can become melodramatic, and guilt you with consequences to make you feel bad about whichever choice you make. That said, I am completely unfamiliar with the wider FMV (Full Motion Video) game genre, so it’s hard to gauge where this sits relative to its peers, only where it lands relative to my experience in the adjacent “choice-based story adventure” and “visual novel and dating sim” categories.

Motesolo follows Kimo, who is a nervous and awkward 29-year-old who has never dated anyone in his life. This is a major insecurity for him, and something he wants to change. He’s tried everything from dating apps to YouTube tutorials to no avail. Our story begins with his friend setting him up on a blind date at a café. You get familiar with what kind of a guy he is by browsing through your phone’s messages, chatting with your friends, scrolling through social media, and watching YouTube for advice. From there, the game will offer you choices on what Kimo does or says, and it’ll determine how successful your afternoon is. There are consequences, but you’re the driver of your story and it’s much easier to own your decisions, rather than feel the game is malicious to the player - they aren’t “hard” decisions, even if it might not be clear which is the best without paying attention to clue.

What I like about Kimo is that he’s neither a self-insert character nor someone that’s trivial to feel sorry for. The guy has several different sides to him, and it’s pretty easy to see several reasons why nobody has wanted to date this guy. What’s interesting is that when you are at a point where you need to make a choice, it feels like you are in control, but then the camera changes angles and Kimo runs with the choice you’ve made which doesn’t always go exactly as you would imagine - sometimes there is no choice that doesn’t end up being awkward to some degree. It’s an interesting way to handle a nervous talker like him, where something sounds good in your head but once you start speaking it may go horrifically wrong. I liked that your choices are not radical departures from his character, but feel more like on-the-spot plausible judgments or sometimes actively restraining Kimo from doing what he’s thinking about doing.

Narratively, the story is very focused. There are side hooks you can optionally pursue (usually based on your optional phone conversations) but the game is clear that these diversions are distractions from your current blind date and reflect what you think is important for Kimo. The comedy is usually self inflicted, prompting an audible “Oh NOOO” from me periodically while playing, and is enhanced by fantastic directing - it’s a genuinely funny game. Kimo’s actor is animated and energetic, absolutely nailing the part. More sincere, personal moments are realistic and can be refreshingly frank. Motesolo spends exactly enough time building the characters that you really do feel like you understand them without piling on exposition (the phone segments’ exploration-style exposition works well here). In my first playthrough, I started off being a bit goofy and clueless, but ended up being invested enough that I tried to turn it around and be a good wingman for our boy Kimo. Failure teaches you what not to do in a way that doesn’t feel arbitrary - for all Kimo’s screw-ups it’s easy to see in hindsight why certain choices were probably a bad idea. The game is good about hinting early, but being more direct later when you missed the hint in case you missed a crucial piece of information. On the other hand, when you do make a bad choice, Motesolo often gives you opportunities to double down on your poor behaviour to much hilarity.

I’m going to compare the game to it’s dating-sim cousin genre for a moment. Using an FMV instead of visual novels’ drawn/rendered characters gives us a huge advantage: reading people. Tim Rogers in his gargantuan review of Tokimeki Memorial, a classic dating sim game, specifically noted that when you make choices in that game, the characters will briefly react with a very quick positive or negative facial animation and that was a design choice that helped give good feedback to the player. Visual novels will have alternate sprites with smiles or frowns to convey character emotions, but nothing comes close to real human body language. At one point in Motesolo, Kimo can choose to take a more assertive action or a safer one. Taking the assertive action prompts a particular reaction from the woman across the table. Her reaction tells us more than just whether she liked or disliked what you did, and without having to explicitly explain it like a visual novel would need to. For example, it’s hard to show the way someone’s eyes look when they’re saying something for their own sake rather than their conversation partner, or the way someone who is nervous has movements that seem overly formal and rigid. By showing rather than telling, communication feels natural and subtle.

Beyond the meat of the game, Motesolo’s interface was surprisingly refreshing. When you boot into the game, there is no main menu. You just go straight into the game’s intro. When you reboot the game, you pick up exactly where you left off. It felt very slick - game developers have certain features you just assume you need in your game by default, but a game like Motesolo honestly doesn’t need a dedicated splash screen, and it streamlined the experience nicely. Everything you need, including the unlock-able bonus content, is accessible from the escape menu if absolutely needed, which can be triggered at all times. It was clean and modern. Any in-game interactions used real-world interactions for familiarity (The one exception being a certain one-off mini-game involving spinning, which stuck out because the game is otherwise so intuitive). I never felt like I needed a tutorial, whether it was the phone segments browsing apps or a surprise quick-time event. Even the choices rarely caught me off guard - they were nearly always subtly telegraphed by good camerawork, the tone of the conversation, and other factors.

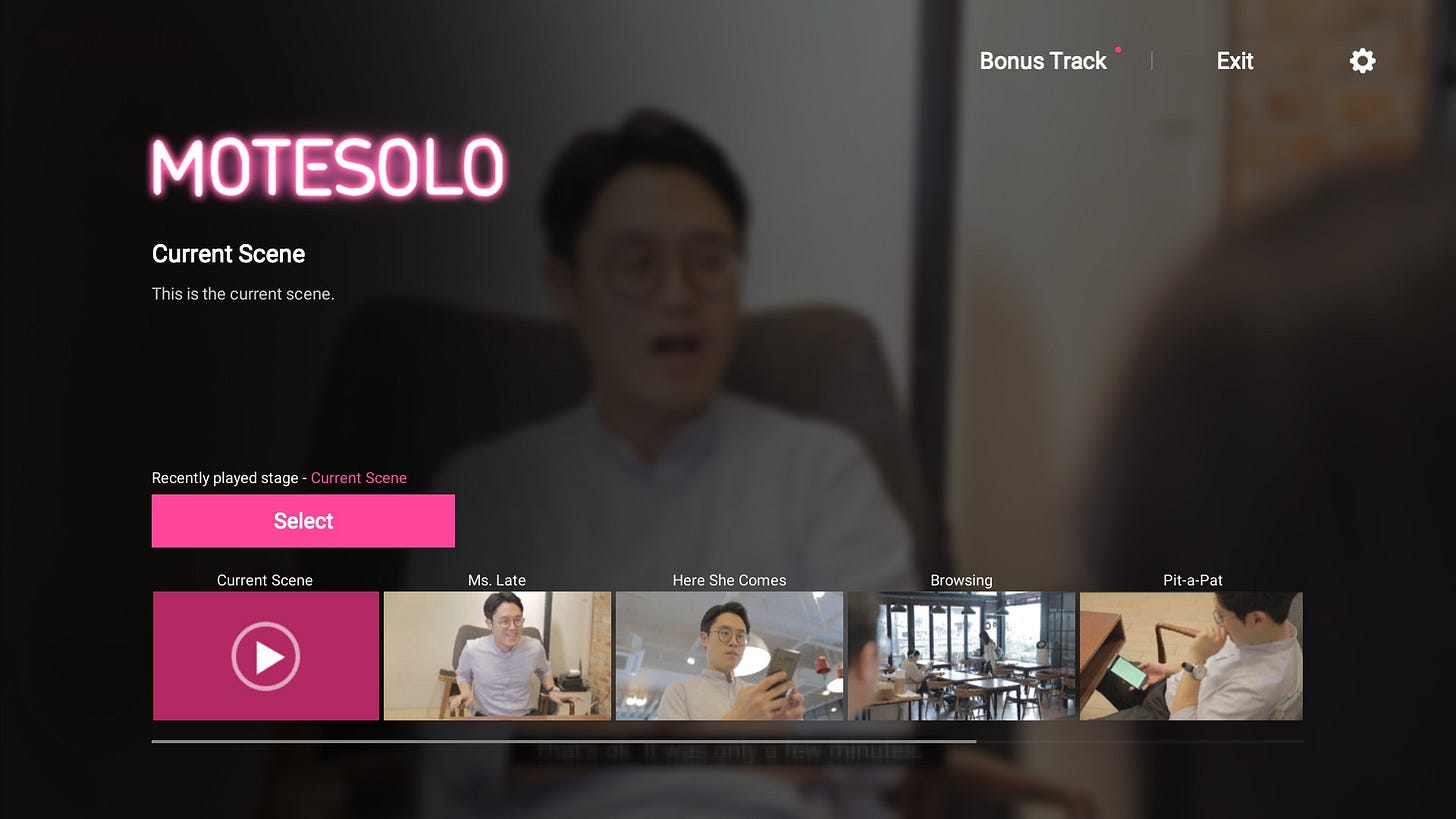

The major interface feature I loved was the scene history. The typical paradigm in visual novels is save game management. You make saves ahead of choices in case you don’t like where the choice was going, or if you want to try replaying from a previous branching point. There’s a concept of “Starting a new game” and doing a playthrough to get certain endings. In some story heavy games, the game is really meant to be played from start to finish as complete playthroughs. While this isn’t necessarily bad, Motesolo instead presents an easily accessible timeline of each scene you’ve played through. You can easily roll back to a previous scene as if you were rewinding playback in a Netflix show, and skip ahead through scenes you’ve already seen (in fact, the whole interface feels more like a streaming TV service instead of a game!). I can’t quite put my finger on it, but there’s a psychological difference between rolling back in this way compared to savegame/fresh playthroughs. It evokes the same feeling that Forza Horizon’s rewind feature has: you’re going back in time to the point your made a mistake, in an effort to do better the next approach. Perhaps its because savegames are premeditated - you must consciously make a save game even if you never need it. It’s a system built on negative anxieties about potentially making wrong decisions even if you only make good ones. Rollbacks in a scene history, on the other hand, are taken as a reaction to bad feelings about a decision you regretted. They also feel better as a means for exploration. You can be curious and click on, say, the “Pipe DIY” option and see what that’s all about without needing to stop and preemptively create saves every time decisions come up to retreat to later.

(I mentioned earlier that Motesolo didn’t feel like it guilted you on making high stakes decisions while still feeling like your choices mattered - scene rollback in this way is an excellent case of mechanics meshing perfectly with narrative design!)

The game manages to have strong replay value by presenting choices that invite you to wonder what might happen if you chose differently. Scene rollback can help integrate this replayability into the same run. After completing a playthrough, you will likely find yourself rolling back to the beginning to see if you can make as many good choices as you can (often enabled by getting to know your date better in your previous run, or realizing you should have paid closer attention to a piece of information) to steadily get further and be rewarded with new scenes you haven’t seen before. The game offers an easy skip button to jump past ones you’ve already scene if you like too.

Overall, Motesolo was a remarkably fun game that I found myself genuinely wanting to try and get good endings without using a guide (I actually never had a choice in this - none of the guides were in English!) after my first failure. The good endings were really special, and when I later chased after some particular bad endings there were some hilarious (tragic?) moments too. My only complaint with the game is that the English translation had several simple typos/errors that could immensely improve the reading experience if an editor looked it over. The translation is otherwise good enough and rarely got in the way of my understanding, but some phrases felt a bit awkward. Beyond that, it’s definitely worth a playthrough at least.

In case you don’t trust my judgment… well, you may have to! A quick google search has literally only came up with just one other review in English for the game outside of Steam, where it has been very well received. That said, Karen seemed to truly love the game as well - a sample size of two ought to be sufficient, right?

Motesolo is available on Steam for purchase, along with a free demo.